Counter racist, codified response to the question, WHO AM I VOTING FOR?

I have been asked several times "Who am I voting for?" I have worked out my own counter racist, codified response.

[Note: NW CP stands for "non-white codified person". A non white codified person is a person who thinks, speaks and acts to reveal truth, promote justice, and eliminate white supremecy]

Person: Who are you voting for?

Non- white codified person (NW CP): Voting for what?

Person: You know, President?

NW CP: President of what?

Person: President of the United States! Duh? Who are you voting for?

NW CP: What is the President of the United States supposed to do?

Person: What the hell kind of question is that? What do you mean, "What is the President of the United States supposed to do?" He's the PRESIDENT. He is the LEADER of the United States.

NW CP: Lead the United States to do what?

Person: What the hell is wrong with you? I just asked who are you voting for!

NW CP: (Silence)

Person: Are you going to vote or what?

NW CP: What is a vote?

Person: Don't play dumb. A VOTE! You pick which one of the candidates you want to be President.

NW CP: What is the President supposed to do?

Person: I just told you. He is the Leader of the United States government.

NW CP: What is the Leader of the United States government supposed to do?

Person: You see, this is what's wrong with America! Fucking idiots like you!

NW CP: (silence)

Person: The government. Do you want the government to be lead by a Democrat or a Republican?

NW CP: I want correct government.

Person: Well who do you think is better, the Democrats or the Republicans?

NW CP: I don't see evidence that either of them have produced justice.

Person: What the hell are you talking about?

NW CP: Justice is guaranteeing that no person is mistreated and that the person that needs the most help gets the most constructive help. As far as I know, the purpose of government is to produce justice.

Person: Look, all I wanted to know was who are you going to vote for.

NW CP: Has any of the candidates produced justice?

Person: (silence)

NW CP: (silence)

Person: (silence)

NW CP: (silence)

Person: You are impossible

NW CP: (silence)

Person: Are you going to vote?

NW CP: No. I don't see the logic in choosing a candidate that hasn't produced justice to lead an incorrect government that produces injustice.

20 REASONS NOT TO VOTE

Written and Compiled by Robert Rorschach.

1. If one votes, one participates. If one participates, one condones and endorses the process, and subsequently, what those elected ‘representatives’ do and say in your name.

2. Electoral promises are meaningless because politicians are able to lie to gain the favour of the electorate, and then do exactly what they want once they have it. Then there is no accountability or recourse, other than waiting another 4 years or so to vote them out and replace them with someone else who will follow the established template and do the exact same thing.

3. The act of voting grants legitimacy to the idea that it’s acceptable for the majority/collective to use the coercive arm of the state to impose their will on the minority/individual using force, or threat of force, and for that reason, it is immoral to vote. As such, the only way to truly de-legitimise the system is by not voting. When the people refuse to participate in droves the international community can no longer recognise the results of the election as legitimate. This perceived legitimacy is such a concern for politicians that in some countries it’s now a legal requirement to vote (e.g., Australia).

4. A non-voter emerges from the electoral process with a clean conscience because they can legitimately proclaim that what the elected ‘representatives’ subsequently say and do after they have gained power is not done in their name, not with their permission, and not with their encouragement.

5. To not vote DOES NOT mean one relinquishes the right to then comment on, complain about, or protest the actions of the government, it is completely the other way round. When one votes one effectively makes a contractual agreement (the voter is officially recorded doing so), which hands over the right for someone else to speak and act in their name, and as such, assents to whatever the government does thereafter. A non-voter however, has not done so, and therefore retains the right to complain, object and protest all they want.

6. Participation in the system (i.e., voting) reinforces the idea that people can’t live together without violent control.

7. Participation in the system (i.e., voting) implies that the majority knows what’s best for everyone.

8. Participation in the system (i.e., voting) implies that the majority knows what’s best for the individual.

9. Voting is effectively participating in mob rule, and the mob then enforces it’s views on the rest of society with the threat of violence.

10. By voting, an individual literally advocates the use of force against peaceful people.

11. Voting reinforces the idea the ‘people’ have the power rather than the largely unaccountable bureaucrats who make the rules.

12. Voting is futile because invariably the better financed candidate wins.

13. Statistically, any one vote makes no more difference than a single grain of sand on a beach. Thinking that their vote counts tends to give the voter a mistakenly inflated sense of self-worth, and participation in a system creates a passive sense of accomplishment.

14. An individual’s ability to make an informed choice is zero if the only information they reference is from the overtly bias main stream media, government news channels (propaganda), politicians and party manifestos (sales pitch), or from an ‘enforced’ state school education (indoctrination).

15. Voting sends a false signal to the elected politicians that the voter approves of all their policies. Voters therefore encourage them.

16. If an individual has not come to firm conclusion about the election, that individual will do more for their country/community by not voting, rather than making a mistake.

17. If the outcome of a vote is unknown, then voting is tantamount to gambling. If the outcome of a vote is known, then voting is futile.

18. No individual has the authority to make laws their neighbour, or anyone else, must obey. Then how is it morally acceptable for any individual to delegate authority they don’t have to someone else, such as a politician?

19. Should people who know more about game shows, sports, reality TV and celebrities, rather than matters of any real importance (economics, political philosophy, history, logic, critical thinking, etc) be in a position to vote and influence the lives of others?

20. Supporting the lesser of two evils is still supporting evil.

The 20 reasons not to vote boil down to this:

If you are not a Voluntaryist, then by definition you are an Involuntaryist, and as such, personally advocate the initiation of force, or threat of force against people who haven’t threatened or harmed anyone. Therefore, for every person in the world one of these statements is true:

1) “I advocate a society whereby people are free to voluntarily interact with one another.”

2) “I advocate the use of force, or threat of force, against innocent people, in order to make them comply with my opinions and preferences.”

If the first statement refers to you, then DON’T VOTE.

First published Thu Jul 28, 2016

This entry focuses on six major questions concerning the rationality and morality of voting:

Is it rational for an individual citizen to vote?

Is there a moral duty to vote?

Are there moral obligations regarding how citizens vote?

Is it justifiable for governments to compel citizens to vote?

Is it permissible to buy, trade, and sell votes?

Who ought to have the right to vote, and should every citizen have an equal vote?

1. The Rationality of Voting

The act of voting has an opportunity cost. It takes time and effort that could be used for other valuable things, such as working for pay, volunteering at a soup kitchen, or playing video games. Further, identifying issues, gathering political information, thinking or deliberating about that information, and so on, also take time and effort which could be spent doing other valuable things. Economics, in its simplest form, predicts that rational people will perform an activity only if doing so maximizes expected utility. However, it appears, at least at first glance, that for nearly every individual citizen, voting does not maximize expected utility. This leads to the “paradox of voting”(Downs 1957): Since the expected costs (including opportunity costs) of voting appear to exceed the expected benefits, and since voters could always instead perform some action with positive overall utility, it’s surprising that anyone votes.

However, whether voting is rational or not depends on just what voters are trying to do. Instrumental theories of the rationality of voting hold that it can be rational to vote when the voter's goal is to influence or change the outcome of an election, including the “mandate” the winning candidate receives. (The mandate theory of elections holds that a candidate’s effectiveness in office, i.e., her ability to get things done, is in part a function of how large or small a lead she had over her competing candidates during the election.) In contrast, the expressive theory of voting holds that voters vote in order to express themselves and their fidelity to certain groups or ideas.

1.1 Voting to Change the Outcome

One reason a person might vote is to influence, or attempt to change, the outcome of an election. Suppose there are two candidates, D and R. Suppose Sally prefers D to R; she believes that D would do a trillion dollars more overall good than R would do. If her beliefs were correct, then by hypothesis, it would be best if D won.

However, this does not yet show it is rational for Sally to vote for D. Instead, this depends on how likely it is that her vote will make a difference. In much the same way, it might be worth $200 million to win the lottery, but that does not imply it is rational to buy a lottery ticket.

Suppose Sally’s only goal, in voting, is to change the outcome of the election between two major candidates. In that case, the expected value of her vote (UvUv) is:

Uv=p[V(D)−V(R)]−CUv=p[V(D)−V(R)]−C

where p represents the probability that Sally’s vote is decisive, [V(D)−V(R)][V(D)−V(R)] represents (in monetary terms) the difference in the expected value of the two candidates, and C represents the opportunity cost of voting. In short, the value of her vote is the value of the difference between the two candidates discounted by her chance of being decisive, minus the opportunity cost of voting. In this way, voting is indeed like buying a lottery ticket. Unless p[V(D)−V(R)]>Cp[V(D)−V(R)]>C, then it is (given Sally's stated goals) irrational for her to vote.

There is some debate among economists and political scientists over the precise way to calculate the probability that a vote will be decisive. Nevertheless, they generally agree that the probability that the modal individual voter in a typical election will break a tie is small, so small that the expected benefit (i.e., p[V(D)−V(R)]p[V(D)−V(R)]) of the modal vote for a good candidate is worth far less than a millionth of a penny (G. Brennan and Lomasky 1993: 56–7, 119). The most optimistic estimate in the literature claims that in a presidential election, an American voter could have as high as a 1 in 10 million chance of breaking a tie, but only if that voter lives in one of three or four “swing states,” and only if she votes for a major-party candidate (Edlin, Gelman, and Kaplan 2007). Thus, on both of these popular models, for most voters in most elections, voting for the purpose of trying to change the outcome is irrational. The expected costs exceed the expected benefits by many orders of magnitude.

1.2 Voting to Change the "Mandate"

One popular response to the paradox of voting is to posit that voters are not trying to determine who wins, but instead trying to change the “mandate” the elected candidate receives. The assumption here is that an elected official’s efficacy—i.e., her ability to get things done in office—depends in part on how large of a majority vote she received. If that were true, I might vote for what I expect to be the winning candidate in order to increase her mandate, or vote against the expected winner to reduce her mandate. The virtue of the mandate hypothesis, if it were true, is that it could explain why it would be rational to vote even in elections where one candidate enjoys a massive lead coming into the election.

However, the mandate argument faces two major problems. First, even if we assume that such mandates exist, to know whether voting is rational, we would need to know how much the nthvoter’s vote increases the marginal effectiveness of her preferred candidate, or reduces the marginal effectiveness of her dispreferred candidate. Suppose voting for the expected winning candidate costs me $15 worth of my time. It would be rational for me to vote only if I believed my individual vote would give the winning candidate at least $15 worth of electoral efficacy (and I care about the increased efficiency as much or more than my opportunity costs). In principle, whether individual votes change the “mandate” this much is something that political scientists could measure, and indeed, they have tried to do so.

But this brings us to the second, deeper problem: Political scientists have done extensive empirical work trying to test whether electoral mandates exist, and they now roundly reject the mandate hypothesis (Dahl 1990b; Noel 2010). A winning candidate’s ability to get things done is generally not affected by how small or large of a margin she wins by.

Perhaps voting is rational not as a way of trying to change how effective the elected politician will be, but instead as a way of trying to change the kind of mandate the winning politician enjoys (Guerrero 2010). Perhaps a vote could transform a candidate from a delegate to a trustee. A delegate tries to do what she believes her constituents want, but a trustee has the normative legitimacy to do what she believes is best.

Suppose for the sake of argument that trustee representatives are significantly more valuable than delegates, and that what makes a representative a trustee rather than a delegate is her large margin of victory. Unfortunately, this does not yet show that the expected benefits of voting exceed the expected costs. Suppose (as in Guerrero 2010: 289) that the distinction between a delegate and trustee lies on a continuum, like difference between bald and hairy. To show voting is rational, one would need to show that the marginal impact of an individual vote, as it moves a candidate a marginal degree from delegate to trustee, is higher than the opportunity cost of voting. If voting costs me $15 worth of time, then, on this theory, it would be rational to vote only if my vote is expected to move my favorite candidate from delegate to trustee by an increment worth at least $15 (Guerrero 2010: 295–297).

Alternatively, suppose that there were a determinate threshold (either known or unknown) of votes at which a winning candidate is suddenly transformed from being a delegate to a trustee. By casting a vote, the voter has some chance of decisively pushing her favored candidate over this threshold. However, just as the probability that her vote will decide the election is vanishingly small, so the probability that her vote will decisively transform a representative from a delegate into a trustee would be vanishingly small. Indeed, the formula for determining decisiveness in transforming a candidate into a trustee would be roughly the same as determining whether the voter would break a tie. Thus, suppose it’s a billion or even a trillion dollars better for a representative to be a trustee rather than a candidate. Even if so, the expected benefit of an individual vote is still less than a penny, which is lower than the opportunity cost of voting. Again, it’s wonderful to win the lottery, but that doesn’t mean it’s rational to buy a ticket.

1.3 Other Reasons to Vote

Other philosophers have attempted to shift the focus on other ways individual votes might be said to “make a difference”. Perhaps by voting, a voter has a significant chance of being among the “causally efficacious set” of votes, or is in some way causally responsible for the outcome (Tuck 2008; Goldman 1999).

On these theories, what voters value is not changing the outcome, but being agents who have participated in causing various outcomes. These causal theories of voting claim that voting is rational provided the voter sufficiently cares about being a cause or among the joint causes of the outcome. Voters vote because they wish to bear the right kind of causal responsibility for outcomes, even if their individual influence is small.

What these alternative theories make clear is that whether voting is rational depends in part upon what the voters’ goals are. If their goal is to in some way change the outcome of the election, or to change which policies are implemented, then voting is indeed irrational, or rational only in unusual circumstances or for a small subset of voters. However, perhaps voters have other goals.

The expressive theory of voting (G. Brennan and Lomasky 1993) holds that voters vote in order to express themselves. On the expressive theory, voting is a consumption activity rather than a productive activity; it is more like reading a book for pleasure than it is like reading a book to develop a new skill. On this theory, though the act of voting is private, voters regard voting as an apt way to demonstrate and express their commitment to their political team. Voting is like wearing a Metallica T-shirt at a concert or doing the wave at a sports game. Sports fans who paint their faces the team colors do not generally believe that they, as individuals, will change the outcome of the game, but instead wish to demonstrate their commitment to their team. Even when watching games alone, sports fans cheer and clap for their teams. Perhaps voting is like this.

This “expressive theory of voting” is untroubled by and indeed partly supported by the empirical findings that most voters are ignorant about basic political facts (Somin 2013; Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996). The expressive theory is also untroubled by and indeed partly supported by work in political psychology showing that most citizens suffer from significant “intergroup bias”: we tend to automatically form groups, and to be irrationally loyal to and forgiving of our own group while irrationally hateful of other groups (Lodge and Taber 2013; Haidt 2012; Westen, Blagov, Harenski, Kilts, and Hamann 2006; Westen 2008). Voters might adopt ideologies in order to signal to themselves and others that they are certain kinds of people. For example, suppose Bob wants to express that he is a patriot and a tough guy. He thus endorses hawkish military actions, e.g., that the United States nuke Russia for interfering with Ukraine. It would be disastrous for Bob were the US to do what he wants. However, since Bob’s individual vote for a militaristic candidate has little hope of being decisive, Bob can afford to indulge irrational and misinformed beliefs about public policy and express those beliefs at the polls.

Another simple and plausible argument is that it can be rational to vote in order to discharge a perceived duty to vote (Mackie 2010). Surveys indicate that most citizens in fact believe there is a duty to vote or to “do their share” (Mackie 2010: 8–9). If there are such duties, and these duties are sufficiently weighty, then it would be rational for most voters to vote.

2. The Moral Obligation to Vote

Surveys show that most citizens in contemporary democracies believe there is some sort of moral obligation to vote (Mackie 2010: 8–9). Other surveys show most moral and political philosophers agree (Schwitzgebel and Rust 2010). They tend to believe that citizens have a duty to vote even when these citizens rightly believe their favored party or candidate has no serious chance of winning (Campbell, Gurin, and Mill 1954: 195). Further, most people seem to think that the duty to vote specifically means a duty to turn out to vote (perhaps only to cast a blank ballot), rather than a duty to vote a particular way. On this view, citizens have a duty simply to cast a vote, but nearly any good-faith vote is morally acceptable.

Many popular arguments for a duty to vote rely upon the idea that individual votes make a significant difference. For instance, one might argue that that there is a duty to vote because there is a duty to protect oneself, a duty to help others, or to produce good government, or the like. However, these arguments face the problem, as discussed in section 1, that individual votes have vanishingly small instrumental value (or disvalue)

For instance, one early hypothesis was that voting might be a form of insurance, meant to to prevent democracy from collapsing (Downs 1957: 257). Following this suggestion, suppose one hypothesizes that citizens have a duty to vote in order to help prevent democracy from collapsing. Suppose there is some determinate threshold of votes under which a democracy becomes unstable and collapses. The problem here is that just as there is a vanishingly small probability that any individual’s vote would decide the election, so there is a vanishingly small chance that any vote would decisively put the number of votes above that threshold. Alternatively, suppose that as fewer and fewer citizens vote, the probability of democracy collapsing becomes incrementally higher. If so, to show there is a duty to vote, one would first need to show that the marginal expected benefits of the nth vote, in reducing the chance of democratic collapse, exceed the expected costs (including opportunity costs).

A plausible argument for a duty to vote would thus not depend on individual votes having significant expected value or impact on government or civic culture. Instead, a plausible argument for a duty to vote should presume that individual votes make little difference in changing the outcome of election, but then identify a reason why citizens should vote anyway.

One suggestion (Beerbohm 2012) is that citizens have a duty to vote to avoid complicity with injustice. On this view, representatives act in the name of the citizens. Citizens count as partial authors of the law, even when the citizens do not vote or participate in government. Citizens who refuse to vote are thus complicit in allowing their representatives to commit injustice. Perhaps failure to resist injustice counts as kind of sponsorship. (This theory thus implies that citizens do not merely have a duty to vote rather than abstain, but specifically have a duty to vote for candidates and policies that will reduce injustice.)

Another popular argument, which does not turn on the efficacy of individual votes, is the “Generalization Argument”:

What if everyone were to stay home and not vote? The results would be disastrous! Therefore, I (you/she) should vote. (Lomasky and G. Brennan 2000: 75)

This popular argument can be parodied in a way that exposes its weakness. Consider:

What if everyone were to stay home and not farm? Then we would all starve to death! Therefore, I (you/she) should each become farmers. (Lomasky and G. Brennan 2000: 76)

The problem with this argument, as stated, is that even if it would be disastrous if no one or too few performed some activity, it does not follow that everyone ought to perform it. Instead, one conclude that it matters that sufficient number of people perform the activity. In the case of farming, we think it’s permissible for people to decide for themselves whether to farm or not, because market incentives suffice to ensure that enough people farm.

However, even if the Generalization Argument, as stated, is unsound, perhaps it is on to something. There are certain classes of actions in which we tend to presume everyone ought to participate (or ought not to participate). For instance, suppose a university places a sign saying, “Keep off the newly planted grass.” It’s not as though the grass will die if one person walks on it once. If I were allowed to walk on it at will while the rest of you refrained from doing so, the grass would be probably be fine. Still, it would seem unfair if the university allowed me to walk on the grass at will but forbade everyone else from doing so. It seems more appropriate to impose the duty to keep off the lawn equally on everyone. Similarly, if the government wants to raise money to provide a public good, it could just tax a randomly chosen minority of the citizens. However, it seems more fair or just for everyone (at least above a certain income threshold) to pay some taxes, to share in the burden of providing police protection.

We should thus ask: is voting more like the first kind of activity, in which it is only imperative that enough people do it, or the second kind, in which it’s imperative that everyone do it? One difference between the two kinds of activities is what abstention does to others. If I abstain from farming, I don’t thereby take advantage of or free ride on farmers’ efforts. Rather, I compensate them for whatever food I eat by buying that food on the market. In the second set of cases, if I freely walk across the lawn while everyone else walks around it, or if I enjoy police protection but don’t pay taxes, it appears I free ride on others’ efforts. They bear an uncompensated differential burden in maintaining the grass or providing police protection, and I seem to be taking advantage of them.

A defender of a duty to vote might thus argue that non-voters free ride on voters. Non-voters benefit from the government that voters provide, but do not themselves help to provide government.

There are at least a few arguments for a duty to vote that do not depend on the controversial assumption that individual votes make a difference:

The Generalization/Public Goods/Debt to Society Argument: Claims that citizens who abstain from voting thereby free ride on the provision of good government, or fail to pay their “debts to society”.

The Civic Virtue Argument: Claims that citizens have a duty to exercise civic virtue, and thus to vote.

The Complicity Argument: Claims that citizens have a duty to vote (for just outcomes) in order to avoid being complicit in the injustice their governments commit.

However, there is a general challenge to these arguments in support of a duty to vote. Call this the particularity problem: To show that there is a duty to vote, it is not enough to appeal to some goal Gthat citizens plausibly have a duty to support, and then to argue that voting is one way they can support or help achieve G. Instead, proponents of a duty to vote need to show specifically that voting is the only way, or the required way, to support G (J. Brennan 2011a). The worry is that the three arguments above might only show that voting is one way among many to discharge the duty in question. Indeed, it might not be even be an especially good way, let alone the only or obligatory way to discharge the duty.

For instance, suppose one argues that citizens should vote because they ought to exercise civic virtue. One must explain why a duty to exercise civic virtue specifically implies a duty to vote, rather than a duty just to perform one of thousands of possible acts of civic virtue. Or, if a citizen has a duty to to be an agent who helps promote other citizens’ well-being, it seems this duty could be discharged by volunteering, making art, or working at a productive job that adds to the social surplus. If a citizen has a duty to to avoid complicity in injustice, it seems that rather than voting, she could engage in civil disobedience; write letters to newspaper editors, pamphlets, or political theory books, donate money; engage in conscientious abstention; protest; assassinate criminal political leaders; or do any number of other activities. It's unclear why voting is special or required.

3. Moral Obligations Regarding How One Votes

Most people appear to believe that there is a duty to cast a vote (perhaps including a blank ballot) rather than abstain (Mackie 2010: 8–9), but this leaves open whether they believe there is a duty to vote in any particular way. Some philosophers and political theorists have argued there are ethical obligations attached to how one chooses to vote. For instance, many deliberative democrats (see Christiano 2006) believe not only that every citizen has a duty to vote, but also that they must vote in publicly-spirited ways, after engaging in various forms of democratic deliberation. In contrast, some (G. Brennan and Lomasky 1993; J. Brennan 2009; J. Brennan 2011a) argue that while there is no general duty to vote (abstention is permissible), those citizens who do choose to vote have duties affecting how they vote. They argue that while it is not wrong to abstain, it is wrong to vote badly, in some theory-specified sense of “badly”.

Note that the question of how one ought to vote is distinct from the question of whether one ought to have the right to vote. The right to vote licenses a citizen to cast a vote. It requires the state to permit the citizen to vote and then requires the state to count that vote. This leaves open whether some ways a voter could vote could be morally wrong, or whether other ways of voting might be morally obligatory. In parallel, my right of free association arguably includes the right to join the Ku Klux Klan, while my right of free speech arguably includes the right to advocate an unjust war. Still, it would be morally wrong for me to do either of these things, though doing so is within my rights. Thus, just as someone can, without contradiction, say, “You have the right to join the KKK or advocate genocide, but you should not,” so a person can, without contradiction, say, “You have the right to vote for that candidate, but you should not.”

A theory of voting ethics might include answers to any of the following questions:

The Intended Beneficiary of the Vote: Whose interests should the voter take into account when casting a vote? May the voter vote selfishly, or should she vote sociotropically? If the latter, on behalf of which group ought she vote: her demographic group(s), her local jurisdiction, the nation, or the entire world? Is it permissible to vote when one has no stake in the election, or is otherwise indifferent to the outcome?

The Substance of the Vote: Are there particular candidates or policies that the voter is obligated to support, or not to support? For instance, is a voter obligated to vote for whatever would best produce the most just outcomes, according to the correct theory of justice? Must the voter vote for candidates with good character? May the voter vote strategically, or must she vote in accordance with her sincere preferences?

Epistemic Duties Regarding Voting: Are voters required to have a particular degree of knowledge, or exhibit a particular kind of epistemic rationality, in forming their voting preferences? Is it permissible to vote in ignorance, on the basis of beliefs about social scientific matters that are formed without sufficient evidence?

3.1 The Expressivist Ethics of Voting

Recall that one important theory of voting behavior holds that most citizens vote not in order to influence the outcome of the election or influence government policies, but in order to express themselves (G. Brennan and Lomasky 1993). They vote to signal to themselves and to others that they are loyal to certain ideas, ideals, or groups. For instance, I might vote Democrat to signal that I’m compassionate and fair, or Republican to signal I’m responsible, moral, and tough. If voting is primarily an expressive act, then perhaps the ethics of voting is an ethics of expression (G. Brennan and Lomasky 1993: 167–198). We can assess the morality of voting by asking what it says about a voter that she voted like that:

To cast a Klan ballot is to identify oneself in a morally significant way with the racist policies that the organization espouses. One thereby lays oneself open to associated moral liability whether the candidate has a small, large, or zero probability of gaining victory, and whether or not one’s own vote has an appreciable likelihood of affecting the election result. (G. Brennan and Lomasky 1993: 186)

The idea here is that if it’s wrong (even if it’s within my rights) in general for me to express sincere racist attitudes, and so it’s wrong for me to express sincere racist commitments at the polls. Similar remarks apply to other wrongful attitudes. To the extent it is wrong for me to express sincere support for illiberal, reckless, or bad ideas, it would also be wrong for me to vote for candidates who support those ideas.

Of course, the question of just what counts as wrongful and permissible expression is complicated. There is also a complicated question of just what voting expresses. What I think my vote expresses might be different from what it expresses to others, or it might be that it expresses different things to different people. The expressivist theory of voting ethics acknowledges these difficulties, and replies that whatever we would say about the ethics of expression in general should presumably apply to expressive voting.

3.2 The Epistemic Ethics of Voting

Consider the question: What do doctors owe patients, parents owe children, or jurors owe defendants (or, perhaps, society)? Doctors owe patients proper care, and to discharge their duties, they must 1) aim to promote their patients’ interests, and 2) reason about how to do so in a sufficiently informed and rational way. Parents similarly owe such duties to their children. Jurors similarly owe society at large, or perhaps more specifically the defendant, duties to 1) try to determine the truth, and 2) do so in an informed and rational way. The doctors, parents, and jurors are fiduciaries of others. They owe a duty of care, and this duty of care brings with it certainepistemic responsibilities.

One might try to argue that voters owe similar duties of care to the governed. Perhaps voters should vote 1) for what they perceive to be the best outcomes (consistent with strategic voting) and 2) make such decisions in a sufficiently informed and rational way. How voters vote has significant impact on political outcomes, and can help determine matters of peace and war, life and death, prosperity and poverty. Majority voters do not just choose for themselves, but for everyone, including dissenting minorities, children, non-voters, resident aliens, and people in other countries affected by their decisions. For this reason, voting seems to be a morally charged activity (Christiano 2006; Brennan 2011a; Beerbohm 2012).

That said, one clear disanalogy between the relationship doctors have with patients and voters have with the governed is that individual voters have only a vanishingly small chance of making a difference. The expected harm of an incompetent individual vote is vanishingly small, while the expected harm of incompetent individual medical decisions is high.

However, perhaps the point holds anyway. Define a “collectively harmful activity” as an activity in which a group is imposing or threatening to impose harm, or unjust risk of harm, upon other innocent people, but the harm will be imposed regardless of whether individual members of that group drop out. It's plausible that one might have an obligation to refrain from participating in such activities, i.e., a duty to keep one's hands clean.

To illustrate, Suppose a 100-member firing squad is about to shoot an innocent child. Each bullet will hit the child at the same time, and each shot would, on its own, be sufficient to kill her. You cannot stop them, so the child will die regardless of what you do. Now, suppose they offer you the opportunity to join in and shoot the child with them. You can make the 101st shot. Again, the child will die regardless of what you do. Is it permissible for you join the firing squad? Most people have a strong intuition that it is wrong to join the squad and shoot the child. One plausible explanation of why it is wrong is that there may be a general moral prohibition against participating in these kinds of activities. In these kinds of cases, we should try to keep our hands clean.

Perhaps this “clean-hands principle” can be generalized to explain why individual acts of ignorant, irrational, or malicious voting are wrong. The firing-squad example is somewhat analogous to voting in an election. Adding or subtracting a shooter to the firing squad makes no difference—the girl will die anyway. Similarly, with elections, individual votes make no difference. In both cases, the outcome is causally overdetermined. Still, the irresponsible voter is much like a person who volunteers to shoot in the firing squad. Her individual bad vote is of no consequence—just as an individual shot is of no consequence—but she is participating in a collectively harmful activity when she could easily keep her hands clean (Brennan 2011a, 68–94).

4. The Justice of Compulsory Voting

Voting rates in many contemporary democracies are (according to many observers) low, and seem in general to be falling. The United States, for instance, barely manages about 60% in presidential elections and 45% in other elections (Brennan and Hill 2014: 3). Many other countries have similarly low rates. Some democratic theorists, politicians, and others think this is problematic, and advocate compulsory voting as a solution. In a compulsory voting regime, citizens are required to vote by law; if they fail to vote without a valid excuse, they incur some sort of penalty.

One major argument for compulsory voting is what we might call the Demographic or Representativeness Argument (Lijphart 1997; Engelen 2007; Galston 2011; Hill in J. Brennan and Hill 2014: 154–173). The argument begins by noting that in voluntary voting regimes, citizens who choose to vote are systematically different from those who choose to abstain. The rich are more likely to vote than the poor. The old are more likely to vote than the young. Men are more likely to vote than women. In many countries, ethnic minorities are less likely to vote than ethnic majorities. More highly educated people are more likely to vote than less highly educated people. Married people are more likely to vote than non-married people. Political partisans are more likely to vote than true independents (Leighley and Nagler 1992; Evans 2003: 152–6). In short, under voluntary voting, the electorate—the citizens who actually choose to vote—are not fully representative of the public at large. The Demographic Argument holds that since politicians tend to give voters what they want, in a voluntary voting regime, politicians will tend to advance the interests of advantaged citizens (who vote disproportionately) over the disadvantaged (who tend not to vote). Compulsory voting would tend to ensure that the disadvantaged vote in higher numbers, and would thus tend to ensure that everyone’s interests are properly represented.

Relatedly, one might argue compulsory voting helps citizens overcome an “assurance problem” (Hill 2006). The thought here is that an individual voter realizes her individual vote has little significance. What’s important is that enough other voters like her vote. However, she cannot easily coordinate with other voters and ensure they will vote with her. Compulsory voting solves this problem. For this reason, Lisa Hill (2006: 214–15) concludes, “Rather than perceiving the compulsion as yet another unwelcome form of state coercion, compulsory voting may be better understood as a coordination necessity in mass societies of individual strangers unable to communicate and coordinate their preferences.”

Whether the Demographic Argument succeeds or not depends on a few assumptions about voter and politician behavior. First, political scientists overwhelmingly find that voters do not vote their self-interest, but instead vote for what they perceive to be the national interest. (See the dozens of papers cited at Brennan and Hill 2014: 38–9n28.) Second, it might turn out that disadvantaged citizens are not informed enough to vote in ways that promote their interests—they might not have sufficient social scientific knowledge to know which candidates or political parties will help them (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996; Caplan 2007; Somin 2013). Third, it may be that even in a compulsory voting regime, politicians can get away with ignoring the policy preferences of most voters (Gilens 2012; Bartels 2010).

In fact, contrary to many theorists’ expectations, it appears that compulsory voting has no significant effect on individual political knowledge (that is, it does not induce ignorant voters to become better informed), individual political conversation and persuasion, individual propensity to contact politicians, the propensity to work with others to address concerns, participation in campaign activities, the likelihood of being contacted by a party or politician, the quality of representation, electoral integrity, the proportion of female members of parliament, support for small or third parties, support for the left, or support for the far right (Birch 2009; Highton and Wolfinger 2001). Political scientists have also been unable to demonstrate that compulsory voting leads to more egalitarian or left-leaning policy outcomes. The empirical literature so far shows that compulsory voting gets citizens to vote, but it’s not clear it does much else.

5. The Ethics of Vote Buying

Many citizens of modern democracies believe that vote buying and selling are immoral (Tetlock 2000). Many philosophers agree; they argue it is wrong to buy, trade, or sell votes (Satz 2010: 102; Sandel 2012: 104–5). Richard Hasen reviews the literature on vote buying and concludes that people have offered three main arguments against it. He says,

Despite the almost universal condemnation of core vote buying, commentators disagree on the underlying rationales for its prohibition. Some offer an equality argument against vote buying: the poor are more likely to sell their votes than are the wealthy, leading to political outcomes favoring the wealthy. Others offer an efficiency argument against vote buying: vote buying allows buyers to engage in rent-seeking that diminishes overall social wealth. Finally, some commentators offer an inalienability argument against vote buying: votes belong to the community as a whole and should not be alienable by individual voters. This alienability argument may support an anti-commodification norm that causes voters to make public-regarding voting decisions. (Hasen 2000: 1325)

Two of the concerns here are consequentialist: the worry is that in a regime where vote-buying is legal, votes will be bought and sold in socially destructive ways. However, whether vote buying is destructive is a subject of serious social scientific debate; some economists think markets in votes would in fact produce greater efficiency (Buchanan and Tullock 1962; Haefele 1971; Mueller 1973; Philipson and Snyder 1996; Hasen 2000: 1332). The third concern is deontological: it holds that votes are just not the kind of thing that ought be for sale, even if it turned out that vote-buying and selling did not lead to bad consequences.

Many people think vote selling is wrong because it would lead to bad or corrupt voting. But, if that is the problem, then perhaps the permissibility of vote buying and selling should be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Perhaps the rightness or wrongness of individual acts of vote buying and selling depends entirely on how the vote seller votes (J. Brennan 2011a: 135–160; Brennan and Jaworski 2015: 183–194). Suppose I pay a person to vote in a good way. For instance, suppose I pay indifferent people to vote on behalf of women's rights, or for the Correct Theory of Justice, whatever that might be. Or, suppose I think turnout is too low, and so I pay a well-informed person to vote her conscience. It is unclear why we should conclude in either case that I have done something wrong, rather than conclude that I have done everyone a small public service.

Certain objections to vote buying and selling appear to prove too much; these objections lead to conclusions that the objectors are not willing to support. For instance, one common argument against voting selling is that paying a person to vote imposes an externality on third parties. However, so does persuading others to vote or to vote in certain ways (Freiman 2014: 762). If paying you to vote for X is wrong because it imposes a third party cost, then for the sake of consistency, I should also conclude that persuading you to vote for X, say, on the basis of a good argument, is equally problematic.

As another example, some object to voting markets on the grounds that votes should be for the common good, rather than for narrow self-interest (Satz 2010: 103; Sandel 2012: 10). Others say that voting should “be an act undertaken only after collectively deliberating about what it is in the common good” (Satz 2010: 103). Some claim that vote markets should be illegal for this reason. Perhaps it’s permissible to forbid vote selling because commodified votes are likely to be cast against the common good. However, if that is sufficient reason to forbid markets in votes, then it is unclear why we should not, e.g., forbid highly ignorant, irrational, or selfish voters from voting, as their votes are also unusually likely to undermine the common good (Freiman 2014: 771–772). Further these arguments appear to leave open that a person could permissibly sell her vote, provided she does so after deliberating and provided she votes for the common good. It might be that if vote selling were legal, most or even all vote sellers would vote in destructive ways, but that does not show that vote selling is inherently wrong.

6. Who Should Be Allowed to Vote? Should Everyone Receive Equal Voting Rights?

The dominant view among political philosophers is that we ought to have some sort of representative democracy, and that each adult ought to have one vote, of equal weight to every other adult’s, in any election in her jurisdiction. This view has recently come under criticism, though, both from friends and foes of democracy.

Before one even asks whether “one person, one vote” is the right policy, one needs to determine just who counts as part of the demos. Call this the boundary problem or the problem of constituting the demos (Goodin 2007: 40). Democracy is the rule of the people. But one fundamental question is just who constitutes “the people”. This is no small problem. Before one can judge that a democracy is fair, or adequately responds to citizens’ interests, one needs to know who “counts” and who does not.

One might be inclined to say that everyone living under a particular government’s jurisdiction is part of the demos and is thus entitled to a vote. However, in fact, most democracies exclude children and teenagers, felons, the mentally infirm, and non-citizens living in a government’s territory from being able to vote, but at the same time allow their citizens living in foreign countries to vote (López-Guerra 2014: 1).

There are a number of competing theories here. The “all affected interests” theory (Dahl 1990a: 64) holds that anyone who is affected by a political decision or a political institution is part of the demos. The basic argument is that anyone who is affected by a political decision-making process should have some say over that process. However, this principle suffers from multiple problems. It may be incoherent or useless, as we might not know or be able to know who is affected by a decision until after the decision is made (Goodin 2007: 52). For example (taken from Goodin 2007: 53), suppose the UK votes on whether to transfer 5% of its GDP to its former African colonies. We cannot assess whether the members of the former African colonies are among the affected interests until we know what the outcome of the vote is. If the vote is yay, then they are affected; if the vote is nay, then they are not. (See Owen 2012 for a response.) Further, the “all affected interests” theory would often include non-citizens and exclude citizens. Sometimes political decisions made in one country have a significant effect on citizens of another country; sometimes political decisions made in one country have little or no effect on some of the citizens of that country.

One solution (Goodin 2007: 55) to this problem (of who counts as an affected party) is to hold that all people with possibly affected interests constitute part of the polity. This principle implies, however, that for many decisions, the demos is smaller than the nation-state, and for others, it is larger. For instance, when the United States decides whether to elect a warmongering or pacifist candidate, this affects not only Americans, but a large percentage of people worldwide.

Other major theories offered as solutions to the boundary problem face similar problems. For example, the coercion theory holds that anyone subject to coercion from a political body ought to have a say (López-Guerra 2005). But this principle might be also be seen as over-inclusive (Song 2009), as it would require that resident aliens, tourists, or even enemy combatants be granted a right to vote, as they are also subject to a state’s coercive power. Further, who will be coerced depends on the outcome of a decision. If a state decides to impose some laws, it will coerce certain people, and if the state declines to impose those laws, then it will not. If we try to overcome this by saying anyone potentially subject to a given state’s coercive power ought to have a say, then this seems to imply that almost everyone worldwide should have a say in most states’ major decisions.

The commonsense view of the demos, i.e., that the demos includes all and only adult members of a nation-state, may be hard to defend. Goodin (2007: 49) proposes that what makes citizens special is that their interests are interlinked. This may be an accidental feature of arbitrarily-decided national borders, but once these borders are in place, citizens will find that their interests tend to more linked together than with citizens of other polities. But whether this is true is also highly contingent.

6.1 Democratic Challenges to One Person, One Vote

The idea of “One person, one vote” is supposedly grounded on a commitment to egalitarianism. Some philosophers believe that democracy with equal voting rights is necessary to ensure that government gives equal consideration to everyone’s interests (Christiano 1996, 2008). However, it is not clear that giving every citizen an equal right to vote reliably results in decisions that give equal consideration to everyone’s interests. In many decisions, many citizens have little to nothing at stake, while other citizens have a great deal at stake. Thus, one alternative proposal is that citizens’ votes should be weighted by how much they have a stake in the decision. This preserves equality not by giving everyone an equal chance of being decisive in every decision, but by giving everyone’s interests equal weight. Otherwise, in a system of one person, one vote, issues that are deeply important to the few might continually lose out to issues of only minor interest to the many (Brighouse and Fleurbaey 2010).

There are a number of other independent arguments for this conclusion. Perhaps proportional voting enhances citizens’ autonomy, by giving them greater control over those issues in which they have greater stakes, while few would regard it as significant loss of autonomy were they to have reduced control over issues that do not concern them. Further, though the argument for this conclusion is too technical to cover here in depth (Brighouse and Fleurbaey 2010; List 2013), it may be that apportioning political power according to one's stake in the outcome can overcome some of the well-known paradoxes of democracy, such as the Condorcet Paradox (which show that democracies might have intransitive preferences, i.e., the majority might prefer A to B, B to C, and yet also prefer C to A).

However, even if this proposal seems plausible in theory, it is unclear how a democracy might reliably instantiate this in practice. Before allowing a vote, a democratic polity would need to determine to what extent different citizens have a stake in the decision, and then somehow weight their votes accordingly. In real life, special-interests groups and others would likely try to use vote weighting for their own ends. Citizens might regard unequal voting rights as evidence of corruption or electoral manipulation (Christiano 2008: 34–45).

6.2 Non-Democratic Challenges to One Person, One Vote

Early defenders of democracy were concerned to show democracy is superior to aristocracy, monarchy, or oligarchy. However, in recent years, epistocracy has emerged as a major contender to democracy (Estlund 2003, 2007; Landemore 2012). A system is said to be epistocratic to the extent that the system formally allocates political power on the basis of knowledge or political competence. For instance, an epistocracy might give university-educated citizens additional votes (Mill 1861), exclude citizens from voting unless they can pass a voter qualification exam, weigh votes by each voter’s degree of political knowledge while correcting for the influence of demographic factors, or create panels of experts who have the right to veto democratic legislation (Caplan 2007; J. Brennan 2011b; López-Guerra 2014; Mulligan 2015).

Arguments for epistocracy generally center on concerns about democratic incompetence. Epistocrats hold that democracy imbues citizens with the right to vote in a promiscuous way. Ample empirical research has shown that the mean, median, and modal levels of basic political knowledge (let alone social scientific knowledge) among citizens is extremely low (Somin 2013; Caplan 2007; Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996). Further, political knowledge makes a significant difference in how citizens vote and what policies they support (Althaus 1998, 2003; Caplan 2007; Gilens 2012). Epistocrats believe that restricting or weighting votes would protect against some of the downsides of democratic incompetence.

One argument for epistocracy is that the legitimacy of political decisions depends upon them being made competently and in good faith. Consider, as an analogy: In a criminal trial, the jury’s decision is high stakes; their decision can remove a person’s rights or greatly harm their life, liberty, welfare, or property. If a jury made its decision out of ignorance, malice, whimsy, or on the basis of irrational and biased thought processes, we arguably should not and probably would not regard the jury’s decision as authoritative or legitimate. Instead, we think the criminal has a right to a trial conducted by competent people in good faith. In many respects, electoral decisions are similar to jury decisions: they also are high stakes, and can result in innocent people losing their lives, liberty, welfare, or property. If the legitimacy and authority of a jury decision depends upon the jury making a competent decision in good faith, then perhaps so should the legitimacy and authority of most other governmental decisions, including the decisions that electorates and their representatives make. Now, suppose, in light of widespread voter ignorance and irrationality, it turns out that democratic electorates tend to make incompetent decisions. If so, then this seems to provide at least presumptive grounds for favoring epistocracy over democracy (J. Brennan 2011b).

Some dispute whether epistocracy would in fact perform better than democracy, even in principle. Epistocracy generally attempts to generate better political outcomes by in some way raising the average reliability of political decision-makers. Political scientists Lu Hong and Scott Page (2004) adduced a mathematical theorem showing that under the right conditions, cognitive diversity among the participants in a collective decision more strongly contributes to the group making a smart decision than does increasing the individual participants’ reliability. On the Hong-Page theorem, it is possible that having a large number of diverse but unreliable decision-makers in a collective decision will outperform having a smaller number of less diverse but more reliable decision-makers. There is some debate over whether the Hong-Page theorem has any mathematical substance (Thompson 2014 claims it does not), whether real-world political decisions meet the conditions of the theorem, and, if so, to what extent that justifies universal suffrage, or merely shows that having widespread but restricted suffrage is superior to having highly restricted suffrage (Landemore 2012; Somin 2013: 113–5).

Relatedly, Condorcet’s Jury Theorem holds that under the right conditions, provided the average voter is reliable, as more and more voters are added to a collective decision, the probability that the democracy will make the right choice approaches 1 (List and Goodin 2001). However, assuming the theorem applies to real-life democratic decisions, whether the theorem supports or condemns democracy depends on how reliable voters are. If voters do systematically worse than chance (e.g., Althaus 2003; Caplan 2007), then the theorem instead implies that large democracies almost always make the wrong choice.

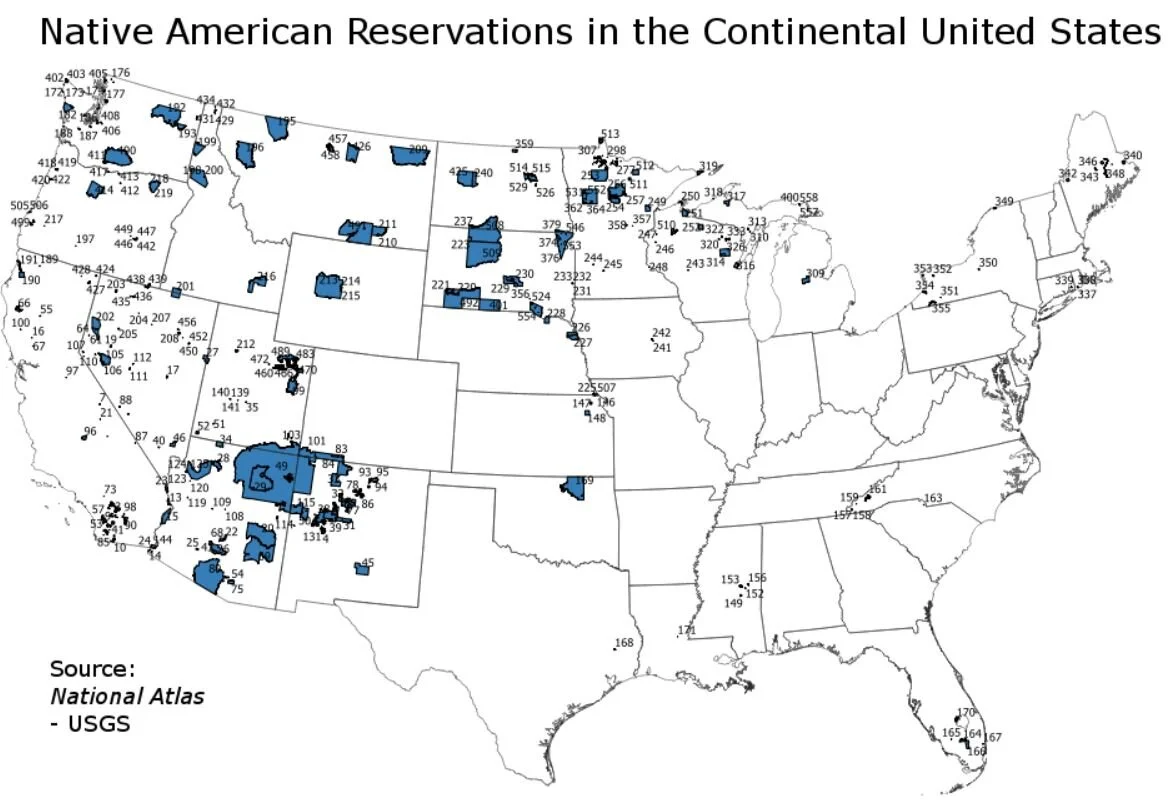

One worry about certain froms of epistocracy, such as a system in which voters must earn the right to vote by passing an examination, is that such systems might make decisions that are biased toward members of certain demographic groups. After all, political knowledge is not evenly dispersed among all demographic groups. On average, in the United States, on measures of basic political knowledge, whites know more than blacks, people in the Northeast know more than people in the South, men know more than women, middle-aged people know more than the young or old, and high-income people know more than the poor (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996: 137–177). If such a voter examination system were implemented, the resulting electorate would be whiter, maler, richer, more middle-aged, and better employed than the population at large. Democrats might reasonably worry that for this very reason an epistocracy would not take the interests of non-whites, women, the poor, or the unemployed into proper consideration.

However, at least one form of epistocracy may be able to avoid this objection. Consider, for instance, the “enfranchisement lottery”:

The enfranchisement lottery consists of two devices. First, there would be a sortition to disenfranchise the vast majority of the population. Prior to every election, all but a random sample of the public would be excluded. I call this device the exclusionary sortition because it merely tells us who will not be entitled to vote in a given contest. Indeed, those who survive the sortition (the pre-voters) would not be automatically enfranchised. Like everyone in the larger group from which they are drawn, pre-voters would be assumed to be insufficiently competent to vote. This is where the second device comes in. To finally become enfranchised and vote, pre-voters would gather in relatively small groups to participate in a competence-building process carefully designed to optimize their knowledge about the alternatives on the ballot. (López-Guerra 2014: 4; cf. Ackerman and Fishkin 2005)

Under this scheme, no one has any presumptive right to vote. Instead, everyone has, by default, equal eligibility to be selected to become a voter. Before the enfranchisement lottery takes place, candidates would proceed with their campaigns as they do in democracy. However, they campaign without knowing which citizens in particular will eventually acquire the right to vote. Immediately before the election, a random but representative subset of citizens is then selected by lottery. These citizens are not automatically granted the right to vote. Instead, the chosen citizens merely acquire permission to earn the right to vote. To earn this right, they must then participate in some sort of competence-building exercise, such as studying party platforms or meeting in a deliberative forum with one another. In practice this system might suffer corruption or abuse, but, epistocrats respond, so does democracy in practice. For epistocrats, the question is which system works better, i.e., produces the best or most substantively just outcomes, all things considered.

One important deontological objection to epistocracy is that it may be incompatible with public reason liberalism (Estlund 2007). Public reason liberals hold that distribution of coercive political power is legitimate and authoritative only if all reasonable people subject to that power have strong enough grounds to endorse a justification for that power (Vallier and D’Agostino 2013). By definition, epistocracy imbues some citizens with greater power than others on the grounds that these citizens have greater social scientific knowledge. However, the objection goes, reasonable people could disagree about just what counts as expertise and just who the experts are. If reasonable people disagree about what counts as expertise and who the experts are, then epistocracy distributes political power on terms not all reasonable people have conclusive grounds to endorse. Epistocracy thus distributes political power on terms not all reasonable people have conclusive grounds to endorse. (See, however, Mulligan 2015.)